1 Introduction

The past decade has seen an explosion of technological innovations, perhaps none of which more seismic for both businesses and individuals than the field of data science. Indeed, the ability to apply advanced analytics to business challenges can be exciting, fruitful and fun. With recent advances in computational capabilities and cost-effective data collection and storage solutions, applying data science to business challenges is now within the reach of most business owners.

Getting started with data science can be daunting, and for the non-specialist, exactly how to begin a data science journey can be unclear. Just like software engineering projects, data science projects require specific design strategies. Our personal experience designing data science projects in a wide range of industries and sectors has given us an understanding of how to make this journey successful and how to work with stakeholders to identify the most impactful business questions and formulate scientific approaches to answer them.

In this book, we share our learnings about sensible approaches to designing data science projects. We offer a framework that we have found to be useful in ensuring successful project outcomes and walk the reader through the process of using this framework for their own data science endeavours. Our goal is to provide a resource that data science practitioners can use in their work and give business leaders an insight into the steps that go into building a data science project from scratch.

1.1 Data science project challenges

For data scientists who are new to the field, perhaps the single most challenging aspect of the role is not technical, but rather conceptual: learning how to design a successful data science project. Often this means breaking down a complex business case into concrete objectives and specific questions. In our roles as mentors and project managers, we too-often see data scientists attack an analysis without first identifying the underlying questions. These can be specific questions about the scientific approach – “What is the hypothesis of this experiment?” or “What statistical question am I asking my model to answer?” – to more general ones such as, “Why are we doing this?”, “What is an ideal outcome?”, “What would constitute a failure?” or “What is the business problem we are trying to solve?” As we tell our mentees, this approach is like building a house without a blueprint: you might hammer together some bits of wood in a useful way, but without understanding the objectives of the project as a whole, success is essentially impossible.

Project design is difficult: it can be loosely structured and often has no single correct answer. This can often be disorienting. How best to approach this task has been considered and discussed often, and many learnings have been derived from the methodologies found in fields such as product design or design engineering. For an excellent discussion of this topic, we recommend episodes 63 - 70 of the podcast Not So Standard Deviations, in which hosts Roger Peng and Hilary Parker discuss the Nigel Cross book Design Thinking and draw parallels to applications in data science.

We often think of data science as a process by which we frame a business problem as a scientific question and apply scientific methodologies to answer that question and derive insights. But how do we identify the business question in the first place? As a data scientist, a good first step is to ask different stakeholders. Yet in our experience, this can often be an unsatisfying approach: more often than not, the stakeholders (clients or managers) will not have a clearly-defined business problem or a concrete objective for the project. We believe our framework can help drive this conversation, setting the stage for well-planned project design and giving projects the best chances for success.

1.2 Data science, machine learning and AI

“Data science”, “machine learning” and “artificial intelligence” are terms that can be used in imprecise ways and can have overlapping meanings. Many will be familiar with the phenomenon of a job advertisement that is billed as a data scientist role but in reality, is more of a data analyst or an IT specialist. AI is perhaps the most liberally-used of the terms, sure to increase one’s chances of writing a successful grant application or tender for a piece of work. It is safe to say that all of these terms can be susceptible to over-hype, and the choice of which to use often appears as a matter of marketing.

But there are differences between them and it’s important to understand what those differences are. One of our favourite discussions about how these terms relate to one another comes from David Robinson:

- Data science produces insights

- Machine learning produces predictions

- Artificial intelligence produces actions

To expand on this slightly, the goal of data science work is to gain insights and understanding into data. While the numerical patterns revealed may be clear and objective, the way these findings are interpreted requires a human in the loop. One way it differs from machine learning is that data science doesn’t necessarily involve modelling. We would also argue that it doesn’t necessarily involve coding or programming: there are plenty of data scientists that combine domain expertise with statistical inference using spreadsheets to acquire valuable insight.

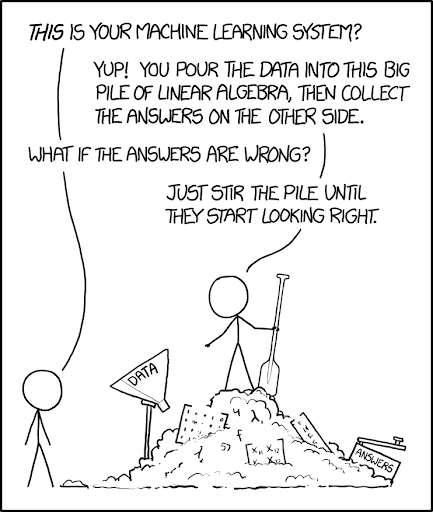

Machine learning extends data analytics into the realm of predictive modelling. This can be done in a highly automated way, although no machine learning system should be allowed to impact decision-making without a human in the loop. Machine learning models can range in complexity and interpretability. For example, linear regression is at the straight-forward end of the spectrum, so much so that many do not consider it machine learning at all. Deep learning models reside at the opposite end of the spectrum, with inner workings that are so opaque that it is essentially impossible to understand how the model makes its predictions. The difference between data science and machine learning is not black and white but rather a spectrum of two overlapping domains.

Figure 1.1: xkcd.com Machine Learning

Artificial intelligence (AI) may be the most commonly-used of the terms and, paradoxically, may also be the most poorly-understood. Many practitioners have strong views on what it means and what distinguishes it from the other two terms. For us, we think of AI as any application that results in an outcome that is an action. This can be anything from robotics used in industries, chatbots providing customer service to game-playing algorithms using reinforcement learning.

For the sake of simplicity, we have chosen to use the term “data science” throughout this book as this most accurately represents the type of projects we tackle. In most cases, the reader can substitute the term with “machine learning” or “artificial intelligence” without losing the message of the text.

1.3 Our framework

Our framework has two related components: project execution and project evaluation. While the temptation may be to view these in series, we have found that these components are intertwined; each has use on its own, but the framework yields the best results when they are used together. In the following chapters, we outline these components, counterintuitively starting with evaluation and then moving on to execution. Why do we start with evaluation? We have found that thinking about what you want the final successful project to look like can help in planning how to get there. In short, we recommend starting with a zoomed-out view of the project as a whole and the context into which it fits before considering the details of how you might get there. We can think of the analogy of taking a road-trip across the country: a sensible approach is to first think about what you want to get out of the journey and what are the major milestones you want to achieve before determining exactly which roads you will take to get there. This has echoes in Test Driven Development (TDD), a common approach to software development in which one first defines the criteria that the final code should adhere to and creates the corresponding tests before writing the actual code.

1.4 Organisation of this book

This book is divided into three main sections. In the Chapter 2 we discuss the four levels of project evaluation in more detail and provides examples of how to assess each. In Chapters 3 through 11 we explain our suggested approach to project design and delivery, breaking the process down into six major phases. We finish by providing some practical tips: Chapter 12 is primarily aimed at independent contractors/freelancers and covers how to build up a client base and find work and Chapter 13 lists some useful resources for where you can find help in the wider data science community.